The UK has a number of distinctive dialects, and Geordie – the dialect of Newcastle-upon-Tyne – is arguably one of our most recognizable. Below you will find phonetic, vocabulary and grammar features of Geordie.

PHONETIC FEATURES

Geordie consonants generally follow those of Received Pronunciation, with these unique characteristics as follows:

- /ɪŋ/ appearing in an unstressed final syllable of a word (such as in reading) is pronounced as [ən] (thus, reading is [ˈɹiːdən]).

- Geordie is characterised by a unique type of glottal stops. /p, t, k/ can all be glottalised in Geordie, both at the end of a syllable and sometimes before a weak vowel.

- T-glottalisation, in which /t/ is realised by [ʔ] before a syllabic nasal (e.g., button as [ˈbʊʔn]), in absolute final position (get as [ɡɛʔ]), and whenever the /t/ is intervocalic so long as the latter vowel is not stressed (pity as [ˈpɪʔi]).

- Glottaling in Geordie is often perceived as a full glottal stop [ʔ] but it is in fact more often realised as ‘pre-glottalisation’, which is ‘an occlusion at the appropriate place of articulation and ‘glottalisation’, usually manifested as a short period of laryngealised voice before and/or after and often also during the stop gap’.This type of glottal is unique to Tyneside English.

- Other voiceless stops, /p, k/, are glottally reinforced in medial position, and preaspirated in final position.

- The dialect is non-rhotic, like most British dialects, most commonly as an alveolar approximant [ɹ], although a labiodental realisation [ʋ] is also growing for younger females (this is also possible by older males, albeit rarer). Traditionally, intrusive R was not present, instead glottalising between boundaries, however is present in newer varieties.

- Yod-coalescence in both stressed and unstressed syllables (so that dew becomes [dʒuː]).

- /l/ is traditionally clear in all contexts, meaning the velarised allophone is absent. However, modern accents may periodically use [ɫ] in syllable final positions, sometimes it may even be vocalised (as in bottle [ˈbɒʔʊ]).

Vowel of Geordie

- For some speakers, vowel length alternates with vowel quality in a very similar way to the Scottish vowel length rule.

- Vowel length is phonemic for many speakers of Geordie and there is often no other phonetic difference between /ɛ/ and /ɛː/ on one hand and /ɒ/ and /ɒː/ on the other. If traditional dialect forms are considered, /a/ also has a phonemic long counterpart (/aː/), but they contrast only before voiceless consonants. There are minimal pairs such as tack /tak/ vs. talk /taːk/ (normal Geordie pronunciation: /tɔːk/). If they are disregarded, this [aː] is best regarded as a phonetic realisation of /ɔː/ in certain words (roughly, those spelt with a). It occurs only in broad Geordie. Another [aː] appears as an allophone of /a/ before final voiced consonants in words such as lad[laːd].

Phonetic quality and phonemic incidence

- /iː, uː/ are typically somewhat closer than in other varieties; /uː/ is also less prone to fronting than in other varieties of BrE and its quality is rather close to the cardinal [u]. However, younger women tend to use a central [ʉː] instead.

- /iː, uː/ are monophthongs [iː, uː ~ ʉː] only in morphologically closed syllables. In morphologically open syllables, they are realised as closing diphthongs [ei, ɵʊ]. This creates minimal pairs such as freeze [fɹiːz] vs. frees [fɹeiz] and bruise [bɹuːz ~ bɹʉːz] vs. brews [bɹɵʊz]. For simplicity, the monophthongal allophone of /uː/ is transcribed with [uː] throughout the article.

- The HAPPY vowel is tense [i] and is best analysed as belonging to the /iː/ phoneme.

- Many female speakers merge /oː/ with /ɔː/, but the exact phonetic quality of the merged vowel is uncertain./øː/ may be phonetically [øː] or a higher, unrounded vowel [ɪː].An RP-like vowel [e:] is also possible.

- Some speakers unround /ɒː/ to [ɑː].Regardless of the rounding, the difference in backness between /ɒː/ and /a/ is very pronounced, a feature which Geordie shares with RP and some northern cities such as Stoke-on-Trent and Derby, but not with the accents of the middle north.

Diphthong of Geordie

- As the transcription indicates, the second elements of /iɐ, uɐ/ are commonly as open as the typical Geordie realization of /ə/ ([ɐ]).

- The first element of /æu/ is phonetically [ä] or [ɛ] or an intermediate [æ]. Traditionally, this vowel was a monophthong [uː] and this pronunciation can still be heard, as can a narrower diphthong [əu].

- /ai/ is phonetically [äi], but the Scottish vowel length rule applied by some speakers of Geordie creates an additional allophone [ɛi] that has a shorter, higher and more front onset than the main allophone [äi]. [ɛi] is used in words such as knife [nɛif], whereas [äi] is used in e.g. knives [näivz]. For simplicity, both of them are written [ai] in this article.

Geordie Dialect Vocabulary

There was, until quite recently, greater lexical diversity across the UK. For centuries, local lifestyles and speech changed very little. Despite a gradual erosion of dialect vocabulary over the course of the twentieth century, one still regularly hears local words and expressions, and Tyneside is a particularly fruitful hunting ground. Much of the local vocabulary is descended from Old English (Anglo-Saxon), but has changed or been replaced in other varieties of English further south. For instance, when a Geordie uses the verb larn, meaning ‘to teach’, it is not a misuse of the Standard English verb learn (c.f. modern German lernen), rather it is the modern reflex of the Anglo-Saxon verb læran, meaning ‘to teach’ (c.f. modern German lehren). Several Geordie words are also thought to have been borrowed from Romany. For example, gadgie, meaning ‘bloke’ or ‘fellow’, is probably an anglicised version of the Romany word used to refer to a ‘male non-Roma’, gadjo (plural gadje). There has been a Roma presence for centuries in the Borders area and so it is not surprising this has influenced speech in the North East.

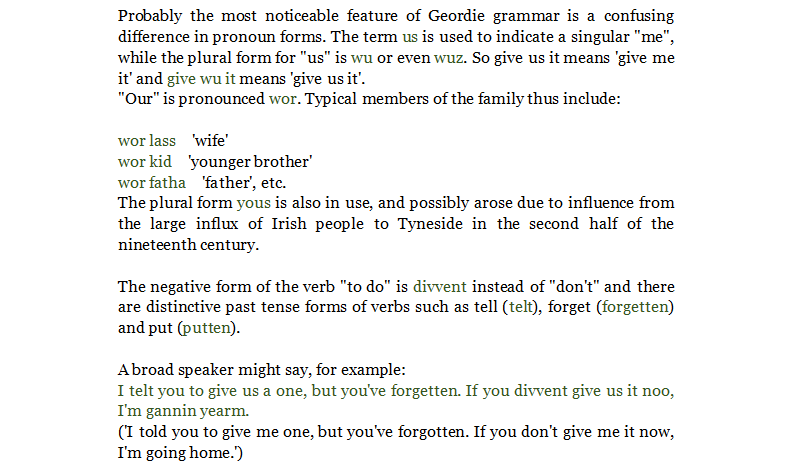

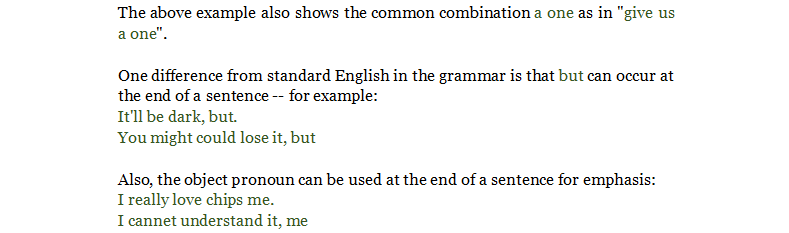

Geordie Dialect Grammar

More examples of regional vocabulary in Tyneside

All are from recent BBC interviews and reflect current usage. They represent natural, authentic usage, rather than reported usage, which can sometimes be exaggerated. The list is by no means comprehensive, and there are numerous other local words commonly used, for example:

fogs — first

burn — stream

bonny — pretty

muckle — very

haway — come on!

canny — quite, really, very

plodge — trudge through thick mud

hadaway — get away’ or ‘you must be joking!

Common Phrase

Hoo ye gannin? ‘How are you?’

Hoo’s ya fettle? ‘How are you?’

Y’areet, hinny? ‘Are you all right, kid?’

Champion. ‘Very good, very well’

Bonny day the day. ‘It’s nice weather’

Cowld the day, mar. ‘It’s cold today.’

Whey aye, man. ‘that’s right’

Give ower, y’a kiddin. ‘Come on, you’re joking’

Hadaway man. ‘I’m still not convinced’

Ya taakin shite. ‘I really disagree with that’

Ootside! ‘Let’s settle this outside’

Hoo’s the Toon gannin? ‘How is the Newcastle United match progressing?’

Tara now, pet. ‘Goodbye (to female)’

Wee’s yon slapper? ‘Who’s the young lady?’ (derogatory)